I know you violently disagree with me already, having just read the title. But stick with me and I will find “the rainbow after the thunderstorm.” And this is a test to see if you read the whole article, or just the headline.

The 2020 Virus

Last year, the virus disrupted lives and livelihoods everywhere. It even caused some marketers to pause their wanton spending in digital. Without this “external shock” most marketers would have been content not rocking the boat and would have carried on as usual. You won’t believe the number of times I’ve heard “it’s got to be working, since we spent money on it.” But spending money on something — like, digital marketing — doesn’t mean it works, let alone works well. Take P&G, Chase, eBay, and Uber for instance. These big brands turned off their digital ad spend and nothing happened to their business outcome? Why? Read the interesting details later, but the short story is that the digital ads they were paying for were not generating the business outcomes they thought they would get. And too often, marketers were assuming that the sales that were happening anyway were somehow caused by the digital ad spending.

But when they paused the digital ad spending and saw no change in business activity, it became clear that the digital ads were not driving incremental sales. In some cases, it was due to ad fraud — where ads were shown to bots and not to humans. In other cases, the lack of business outcomes was due to waste — ad dollars going to ad tech middlemens’ pockets instead of towards showing ads [1]. In still other cases, it was due to incorrect or inaccurate targeting because the data was crappy [2]. And finally, in some cases, ad tech companies were claiming credit for sales that had already happened, by tricking the analytics and attribution platforms [3]. It’s all bad. And the virus caused marketers to find this out; they would never have voluntarily paused their digital ad spending otherwise.

The Privacy Regulations

Most marketers have heard of GDPR (General Data Protection Regulations) and CCPA (California Consumer Privacy Act). These regulations are the beginning of a pendulum swing towards privacy, for the consumer. The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal of 2016 brought to the forefront of everyone’s minds the fact that ad tech companies had been harvesting, selling, and using consumers’ data without their knowledge, consent, or recourse. Even if the data were completely wrong, the consumer would have difficulty finding out, correcting it, or requesting ad tech companies to stop using and selling it.

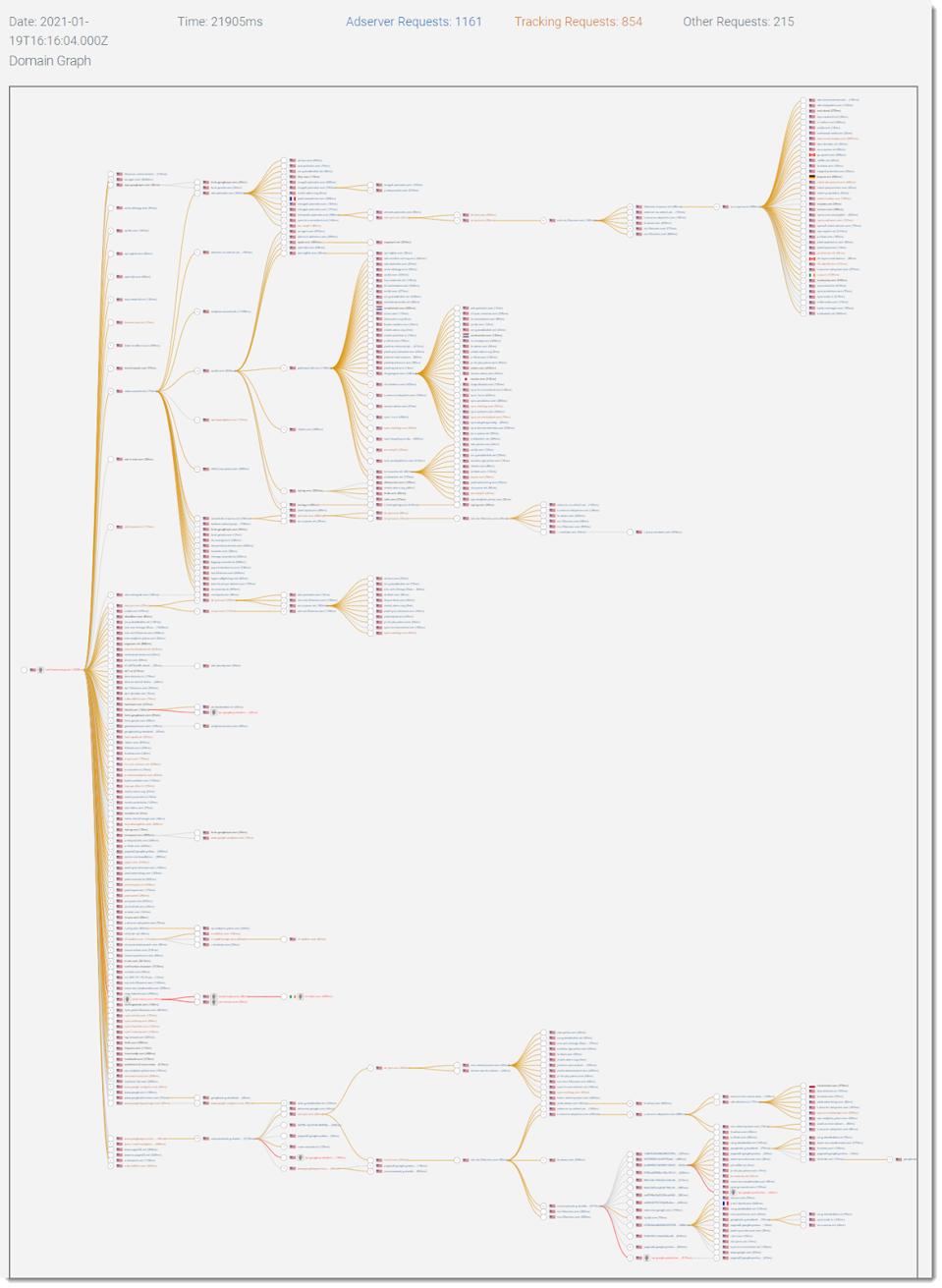

The privacy regulations are a step in the right direction, but by no means efficacious for consumer privacy. That’s because there are different interpretations of it, and it will take years to test it in court before anything’s decided or truly enforced. In the meantime, consumers’ privacy is still “leaky” at best. But the fact that regulations are being enforced and fines being levied means that some companies are choosing to do the right thing, to comply with the law. They are gathering consent from users where possible, and this process raises consumer awareness of the problem further. Consumers had already been protecting themselves from too-many-ads by using ad blockers. Those same consumers are using ad blockers even more to block the ad trackers too, of ad tech companies they’ve never heard of, let alone given consent to. One glance at the following PageXray by FouAnalytics reveals well over 2,000 ads and trackers served into a single page of what is considered a mainstream site — smithsonian.com. Consumers know they are interacting with Smithsonian; but they certainly don’t know any of the ad tech companies whose code is on the page and harvesting their data without consent.

PAGEXRAY BY FOUANALYTICS

As more consumers opt-out and block ads and trackers, marketers will realize that the behavioral targeting and hyper targeting they bought into was not working as well as the ad tech companies had promised. They may even find that the targeting is completely wrong and worse than no targeting at all [4] — for example if the ad tech data got gender right only 41% of the time, it would have been better to “spray and pray.” Those untargeted ads would have reached the 50% correct target — males — anyway; and you would not have paid extra for the data. Privacy regulations, even if just the start, are exposing marketers to the reality versus the hype of programmatic ad tech. So some of them are being more “thoughtful” in what they pay for going forward.

English

English French

French German

German