News recently broke that the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) had been procuring location data from millions of mobile devices to study how COVID-19 lockdowns were working.

Appalled opposition MPs called for an emergency meeting of the ethics committee of the House of Commons, fearing that the pandemic was being used as an excuse to scale up surveillance.

At the same time, our group of interdisciplinary experts from around the world convened at a research retreat on the subject of the ethics of mobility data analysis. Computer scientists, together with philosophers and social scientists, looked at the ethical challenges posed by the uses of mobility data, especially those legitimized by the pandemic.

The collection and use of location data

Telecommunications providers like Telus and Rogers know where cellphones are located by triangulation from the cell towers to which each phone connects. The data is a commodity and they share it, in anonymized form, with others, including academics.

Smartphones can also use the global positioning system (GPS) or their connection to Wi-Fi access points to collect location data and share it with companies to receive customized services, like navigation or recommendations.

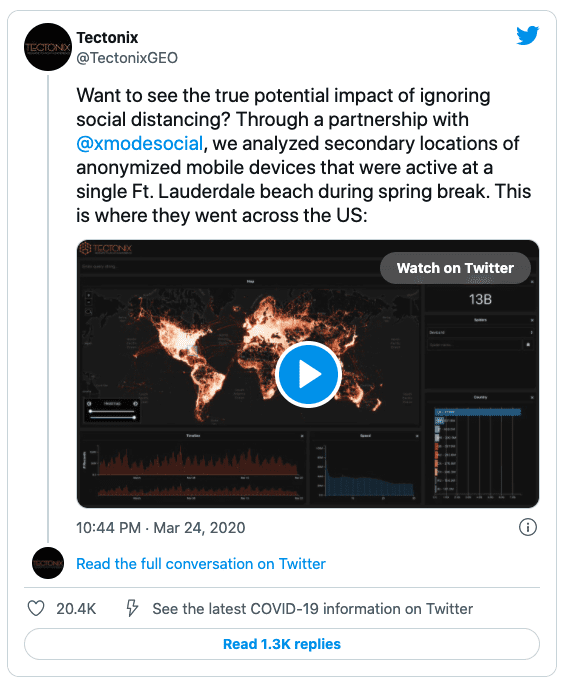

Many companies are interested in gathering location data even when their services don’t require it, as selling that data to other companies is an attractive prospect. For example, Tectonix tweeted in 2020 about a dashboard it had developed with data acquired from X-Mode to track the cellphones of people who partied on a Fort Lauderdale beach during spring break in March.

Not so anonymous

Companies and data brokers may claim to only store or sell anonymized location data, but that’s little comfort when location data itself is so identifiable and revealing. In particular, and contrary to popular belief, it’s almost impossible to make detailed location data truly anonymous. Even if a sequence of locations visited by an individual is stripped of any connection to that person’s name or other identifiers, the possibility of re-identification due to the inherent information contained in this trajectory must be considered.

It becomes quite simple to look up who lives at a given location and assume that where someone spends their days is their work, and where they are in the evenings is their home, and this can uniquely identify a person.

Similar to records of a person’s online activities, the places visited can also reveal sensitive data such as health (repeated visits to a particular clinic), religion, hobbies and family (where your children go to school). Location data is hard to anonymize and can be used to re-identify a person, and all sorts of other information can be inferred from patterns of movement.

Government agencies like PHAC want to use mobility data to understand trends in the “movement of populations during the COVID‑19 pandemic” to study how the disease spreads and also to monitor how measures put in place, such as the confinement, are respected by the population.

The fear expressed by Conservative and Bloc Québécois members of Parliament is that the government is using the pandemic to justify a new level of surveillance of Canadians that could continue even after the pandemic is over.

English

English French

French German

German